Why this mad rush?

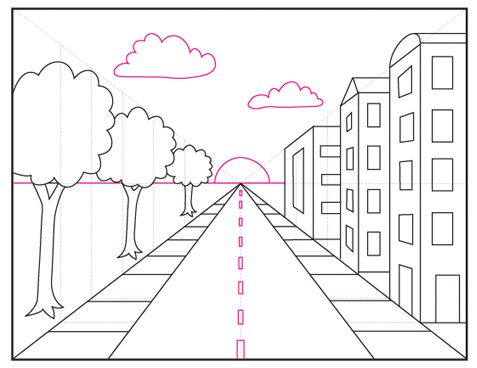

Image-1

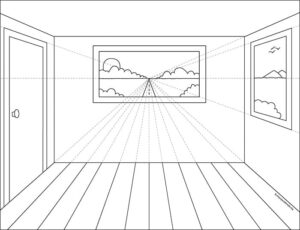

Image-2

I have been observing a trend both in schools and other art class setups – a rush to introduce ‘one-point perspective’ to learners as young as eight years old (class 3 or 4 onwards). Why am I discussing this? In order to delve deeper into this, let me first explain what is done while introducing a concept like one-point perspective.

A diagram or template like image 1 & 2 is shown. Children are asked to use a scale to draw something similar. A definition like this is usually read out – ‘One point perspective is a drawing method that shows how things appear smaller as they get further away, converging towards a single ‘vanishing point’ on the horizon line. It is a way of drawing objects upon a flat piece of paper (or other drawing surface) so that they look three-dimensional and realistic.’

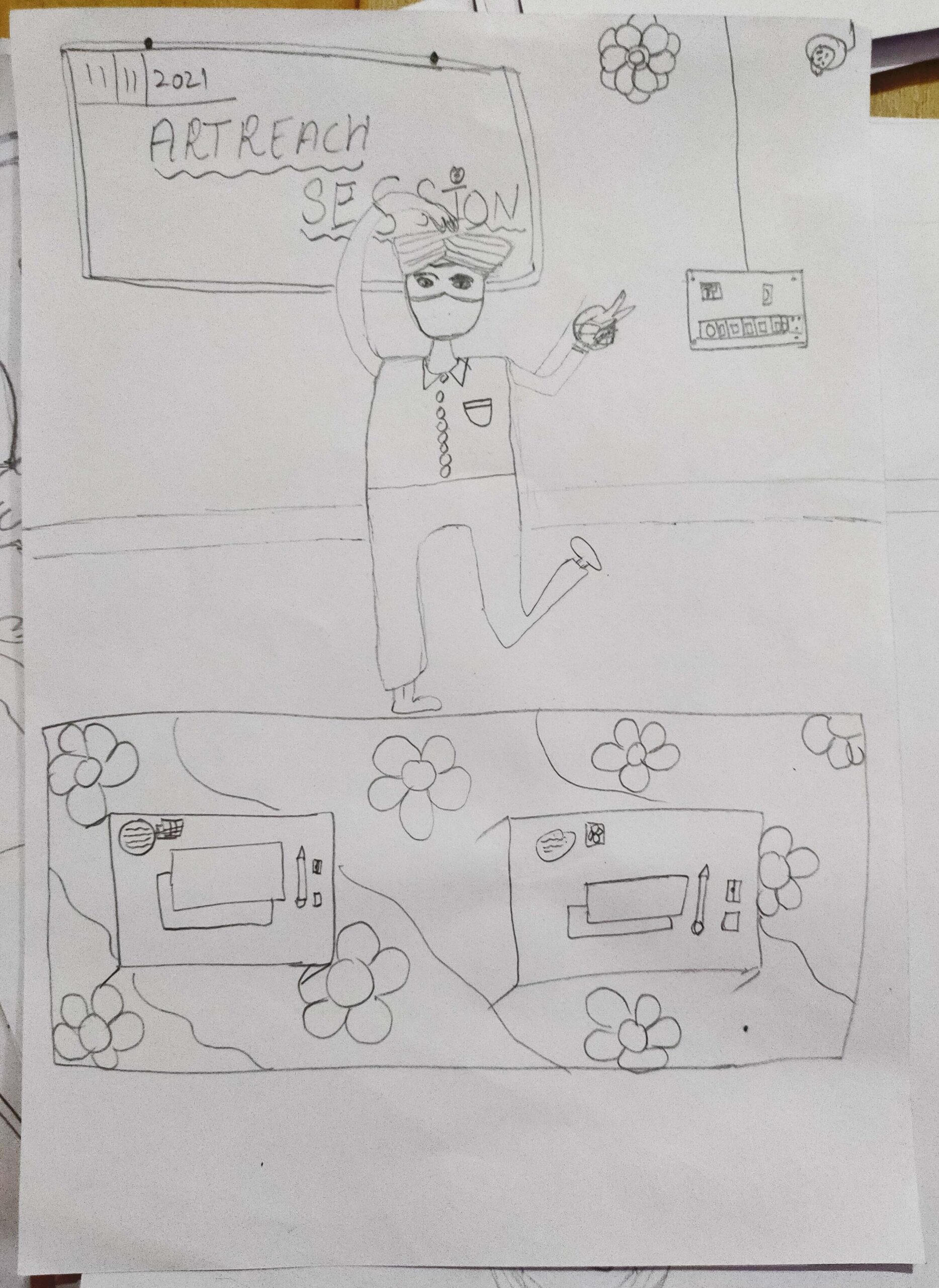

Image-3

Image-4

A few art teachers mention the example of how a long road appears to converge at a distance (image 3). Children that young, mostly copy the template. Very few understand it and are hardly able to apply it in a different situation(image4).

Rarely the reasons behind why we need to know this is explained properly. The experience of what is the difference between an object lying close-by versus the same object kept far off and how to show this difference while drawing are hardly taken up. Sketching and recording such observations are rarely considered an important step.

The children are hardly engaged in experiencing and recording an object or a form at different eye-levels. Imagine what fun it will be if all twenty to twenty-five young ones in the group investigate forms at different eye-levels. Some standing on their chair to observe from above, a few seated on the floor to see from below the eye-level or a few moving the object to record it. Instead, diagram like image 5 are provided.

Image-5

I must add here, usually one topic is taken up over two to three art classes. Investing more time than this is not possible. Often quantity takes over everything else in an always productive work culture. Besides that, preparatory drawings, sketching to record or scribbling while thinking are rarely considered as desirable outcome of any exercise in an institutional setup. There is immense pressure for something spectacular all the time. Besides these institutional limitations, I am interested in understanding the reasons behind choosing such topics for young learners. Where is it coming from?

Image-6

Often, children till classes 3 or 4, sometimes even after that draw the ground at the very bottom of the sheet and sky at the top. While colouring, many leave the space in-between blank (image 6). When asked about the blank space, mostly there is no answer. Once in a blue moon, you may find a young one in your class who may reply that the space is air. When asked, mostly children respond by saying ‘I will fill it with different colours or patterns.’ To nurture a query like this in a child is of great value according to me. This liminality can initiate a lot of inquiry if sensitively taken up from time to time. The unpredictability is very playful in those formative years. Usually, we grownups are scared of such open-endedness while children comfortably navigate such processes. Sometime they draw the wall, the ceiling and the floor of an indoor space all together. Though many among art teachers enjoy that but ultimately, it is not correct (image 7 & 8). It has to change.

Children spontaneously draw things they know well. The details they include are impeccable. However, they don’t shy away from drawing something they are yet to understand or don’t remember too well. Their visual interpretation is playful and reflects their ways of thinking. Sometimes they think and draw in ways that don’t exist in the world around us. At that stage, it is not important whether the end product is convincing according to the criteria of the so-called REAL. What is important is to activate ways of thinking? In our curriculums, we hardly give any importance to the scribbles, dots and lines drawn by children in their elementary years where every single mark is drawn with a reason or there’s some story behind it. We impatiently wait for that phase to get over and the next phase of drawing recognizable things to begin. During this period, book illustrations, worksheets overcrowded with clip-art and images from mass-media condition the seeing and the drawing. We are hardly able to build on those abstract thoughts and accordingly the image making.

In my interaction with art teachers in schools, academies and hobby classes, I have often observed a sense of accomplishment to be able to take up one-point perspective. It is considered as essential to impart ‘SKILL’ and to make ‘REALISTIC’ drawings. As if, this is a magic tool. Using this, a young learner will surely produce realistic or real looking rose, fish, human figures etc. Another justification is that some of these things are vital components of art syllabus at +2 levels and further required for entrance in art colleges.

I am looking at this obsession as a colonial hangover as well. In our art colleges (from where a huge number of pass outs take up teaching art in schools as a profession), there is a hero worshipping of the works of Renaissance artists. The canons of one-point perspective, magic realism, photo-realism and so on is considered immensely important. Achieving a kind of visual likeness or a photograph like finishing becomes the ultimate aim of drawing and painting. It is considered REAL or CORRECT.

Image-7

Image-8

Along with works of classical masters, if equal enthusiasm is shown in exploring multiple perspectives in traditions like the miniature paintings, folk /tribal art traditions or outsider art, a young art graduate will encounter, investigate and understand in myriad ways. What about child art? What about works of artists whose engagement is beyond the tenets of the so-called real? It helps in making connections between distinct ideas. Then the process of seeing, experiencing and creating will become constantly evolving. Equipped with an inclusive approach like this, I am sure teaching how to make REAL/CORRECT drawings will transform into something else.

A conservative understanding of what is meaningful or worth learning limits the process of exploring by a young learner. It also limits the purpose of the exercise taken up. Knowing a concept to understand it’s usage in the world around us is completely different from copying a template. A lot of parents worry that their children cannot draw the human figure or the animal form properly. Gradually, it becomes my child doesn’t draw too well. Then comes the stage of copying from ‘how to draw/paint’ videos on the internet. Before copying or practicing from some reference do we give some time to think why we need to copy? What are we trying to achieve by doing this? What kind of reference is worth copying?

Not only one-point perspective, there is a fast forwarding of several other concepts, topics and even medium used. As an experience to see, think, wonder and play will become meaningful when enough thought is given to the basic ‘What? Why? How?’ What is the nature of engagement and what is the final outcome expected – are essential questions that the art teacher needs to consider beforehand. There needs to be a lot of dialogue between the art teachers from distinct set ups. In out art colleges, there is hardly any discussion on art education especially regarding engaging young children with art. When the young art graduate becomes a teacher, they pass on the same stereotype to the young ones in their classrooms which they experienced in the colleges. Readymade templates and internet full of ‘how to do’ videos hardly address these questions. In our schools or other setups, mostly teachers follow rather than creating own content. When they create, there is very little meaningful support. Most of the training is from a perspective that the teacher doesn’t know much which in many cases is true because the training they received in their school and college rarely addressed these concerns. The same institutional lacuna in understanding a learner is applied on the teacher-learner in this case. Maybe, my thoughts are a little mixed up as these are all inter-related and one thing leads me to the other.

Credit: I thank all my young learners, their parents, schools and other organizations I have worked with for letting me document and use the children’s work to illustrate my understanding around art education practices.